Evolutions

On this page, the intention is to give some broader, additional Information to supplement that given on other pages of the site. To help make the art process more accessible, and to help choose what type of painting may better suit your needs, some of the works are shown in greater detail , with some insight into their inspiration, the creation process and a description of the techniques and differences between the two principal medias of Oil and Watercolour.

Oil v Watercolour

Oil is generally the media of the old masters and most of the famous paintings you can think of off the top of your head (Da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’; Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’; Edward Hopper’s ‘Nighthawks’ etc.) are oil paint on canvas, although most famous artists worked to some degree in both mediums. Oil is usually applied either using a brush or a palette knife; Van Gogh was a great exponent of the palette knife; and Lisa generally applies the oil to her paintings with a brush. The substrate itself is usually canvas applied to a stretcher, which is a wooden frame with small wedges in each corner which can be forced into the corner, thus pushing the sides of the frame further out and ‘stretching’ the canvas. Most of Lisa’s Koi paintings are done this way. The larger commissions, such as ‘Jungle’ and ‘Bayeux Tapestry’ are canvas applied over board which gives the larger paintings stability. Older paintings seen in art galleries are generally framed, sometimes very ornately, but Lisa prefers the more modern approach of not framing oils and returning and painting the canvas on the edges. They can be framed if required. Oil paintings take time to dry, have a linseed oil smell for most of their lives and the surface can get dusty and can be vulnerable to damage if placed in a high traffic area with people passing.

Watercolour has been around since the beginning of art but was not really common until the beginning of the 16th century with Albrecht Durer being an early exponent with small studies such as ‘Hare’ (1502). It remained a minor discipline until the late 18th century when it was picked up by William Blake to hand colour etchings, with works such as ‘The Ancient of Days’ (1794) and J.M.W.Turner, who found it the ideal medium for ‘plein air’ painting and the rendering of dramatic and atmospheric seascapes and skies. Being very accessible and quick drying, it would be common for an artist to flesh an idea in watercolour as a sketch, even when this was not the intended final media, and then return to the studio environment to produce the piece as an oil work. An example is shown here of ‘Les Flamant Roses, in both watercolour and oil forms.

Lisa still does some paintings in both medias; generally trying an idea out in watercolour and then committing to a larger oil. Watercolours start off with stretching a piece of paper by immersing it in water, waiting for the paper to expand, and then fixing it to a wooden board with gummed paper around the perimeter. As the paper dries, it shrinks back and becomes tight, like a drum skin. The watercolours are then applied to the paper, usually starting with a thin wash over the whole to establish a back ground colour, then applying the further colours over the top to provide the detail of the subject. A special liquid can be applied to the paper in certain areas to prevent the background wash sinking into the paper. When the background has dried, this masking fluid can be rubbed off leaving a ‘hole’ in the background so that different colours of the paintings detail can be applied. If the paper was not stretched on a board at the start, the wet paint (essentially coloured water) would cause the paper to expand or cockle and the painting would not be flat. When complete and dry, the paper is cut off the board, the painting is then put under a mount to give a neat edge to the painting all round and then framed.

For Lisa’s work, the major difference between oils and watercolours is that watercolours are framed and mounted under glass. Oils are usually larger and, generally more expensive. Lisa’s work can be produced in whichever medium is more suitable to your requirements.

Inspiration

In the naturalistic section of Lisa’s work, the inspiration for the paintings comes from the way animals use colour or texture or shape to camouflage themselves or communicate in social groups. ‘Les Flamant Roses’ is inspired by a flock of Flamingos; ‘Rhamphastos Toco’ by the beak of a Toucan.

The meaning of each painting is generally very well disguised, only to become more obvious when explained. ‘Camelopardalis’ (the Giraffe codenamed Gerald among Lisa’s friends) is very rare among her work in being completely obvious as to what the subject matter is. In the ‘Taxa’ group, one of the panels is called ‘Tyto Alba’ and this depicts the wing of a Barn Owl. When Lisa’s studio was being built, before the ceiling was finished and the windows installed, a Barn Owl was discovered one morning roosting on the ceiling beams. The owl was left to sleep all day and then it went on its way once dusk started to fall. Lisa has always taken this as a good luck omen.

Ernest Dade

Ernest Dade was an English painter, specialising in coastal and maritime scenes and also a professional model ship maker. He was born in 1864 in Kensington, London. He was one of the founder members of the Staithes Artists Group, which was based in the small Yorkshire fishing village. He exhibited works at the Royal Society of British Artists, the New English Art Club (of which he became a member in 1887) and the Royal Academy of British Artists (from 1887 to 1901) among others.

Ernest’s father, Frederick Dade (1836 – 1874) was a professional photographer and his mother was Matilda Toye-Dade (1835 – 1919). Ernest’s oldest Sister, Emma, was Lisa’s great grandmother, making Ernest Lisa’s great, great Uncle. Ernest had a younger brother, Fred Dade, who was also an artist of repute. The National Maritime Museum holds both brothers works in its collection, including a large number of Ernest’s sketch books.

When he was a young boy, Lisa’s Father met Ernest and remembers being given a model boat that they sailed together on the Serpentine.

Ernest died in 1936.

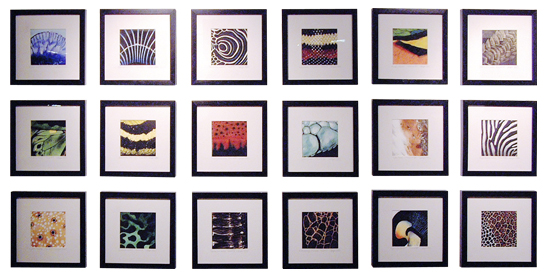

Taxa

‘Taxa’ (2004), is a large work which is actually made up of 18 individual watercolours. Taxa comes from Taxonomy, itself from the Ancient Greek meaning ‘arrangement’ and ‘method’ and is the academic discipline of defining groups of biological organisms in a hierarchical classification on the basis of shared characteristics. All living organisms alive or extinct are classified using this system and are broken down into 6 Kingdoms: Bacteria, Protozoa, Chromata, Plantea, Fungi and Animalia. Each Kingdom is further subdivided into Phylum and each Phylum into classes and so on, refining down into smaller groups until all are categorised by their shared characteristics. Lisa is interested in the Kingdom Animalia, and Taxa features 5 classes from the Phylum Chordata; mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish, and 3 classes from the Phylum’s Mollusca, Cnidaria and Insecta.

Taxa’s 18 panels are all individually framed, approximately 300mm square, and can be purchased individually or in groups or as the whole set of 18. Each panel can also be reproduced at any size in either watercolour or oil. It is Lisa’s intention to produce this piece as a major series of oils in the future.

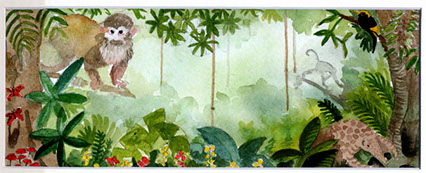

Jungle

‘Jungle’ (2003), is a 14 foot by 4 foot oil on canvas work commissioned by a hospital trust at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Harlow, Essex. The work is painted in Acrylic with oil paint being used for the detail of the animals depicted. The canvas is directly adhered to a hardboard backing fixed to the frame, giving such a large paintings more stability.

The initial brief for this commission was for something big and bright for children to look at while families visited loved ones while they were in hospital. It was to be positioned in a family visiting room. Lisa had devised a sketch for an earlier enquiry to produce an artwork to provide the backdrop for a ball swamp at a leisure centre. This work was to be for two sides of the area meeting in the corner and the description of a ball swamp suggested to Lisa a jungle scene with brightly coloured animals in it. This earlier commission was never taken up but Lisa had kept the sketch illustrating the work and pitched the idea to the hospital group who thought the idea was just what they wanted. They also requested that a smaller version of the painting be provided with all the animals and plants named and indicated so that children could spot them on the painting and tick them off on a sheet. The painting was completed, with the smaller version framed on the wall beside it, and continues to be enjoyed by children and adults visiting the hospital.

Sagittal Suture

In common with a lot of artists, Lisa’s formal art education involved sketching and painting a lot of challenging 3 dimensional objects, including skulls. This resulted in a lifelong interest in natural history and skulls in particular, and she has a fairly extensive collection; a hobby some people find slightly macabre. Sagittal Suture is a succession of paintings directly influenced by this collection and Lisa has been exploring the line formed on the top of the skull, which is actually a dense, fibrous connective tissue joint between the parietal bones of the skull. Lisa describes that what interests her most about the line is that, at first, it appears to be quite simple but, when inspected more closely, it is incredibly intricate and complex.

Back to top

All images and artwork depicted on this site are copyright Lisa Rippon

Web design by Arborial Arts